Liverpool Post 9th April 1925 from a Correspondent.

Motorists usually think of villages in terms of one dimension and conceive of them as possessed of length without breadth

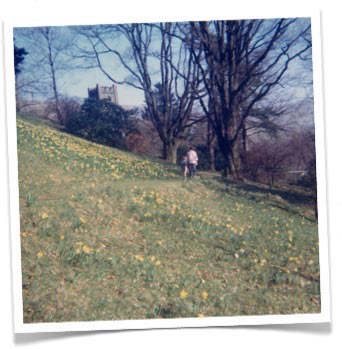

The thousands of people in cars who pass through Rydal in times of holiday see this ancient settlement as a length of narrow road with curves opened upon by stone porches and garden gates which are presumably sometimes entered and left though few motorists have seen this precarious process on operation They remember it as a place where pedestrians when not flattening themselves against the grey stone walls cause aggravating traffic complications at the bends. They may, if they be observant, also be aware of the vicarage garden a slope of lawn and rocks “daffodils and prim roses and of a by-road that turns uphill but beyond this they realise nothing except that Ambleside is behind and that Grasmere lies ahead.

The true Rydal is withdrawn from the motorist and know him but as a distant hum - even soothing in warm - weather as an intermittent rush and glitter seen far below between tree trunks. Rydal sits above the main road on the knees of the fells and serene amid the drowsy clamour of its rookery and its memories of prehistoric man, cherishes within it the Rash Field.

To the passer-by on the main road this enclosure appears but as a tweeting glimpse of daffodils, thousands of little wild Lent lilies climbing a green slope.

Wordsworth bought the field long ago so that he could build himself a house on it in the event of his having to leave Rydal Mount. However he

remained in occupation of the latter" ancient dwelling place until his death and the field below it is tenanted but by daffodils, many planted and all cared for by the Poets grandson. Some brought from the shore of Ullswater, must be the direct descendants of that “host of golden daffodils” that delighted William and Dorothy one Easter time more than 120 years ago.

The gate to the Rash Field is locked. But those who are privileged to borrow the key enter into enchantment. From the gate a winding path of mown green grass leads up the hillside amid grey rocks and great oaks, contemporaries no doubt of the rushes that gave the field its ancient name.

These oaks belong to a vanished order of things. From them and their brethren that grew all up the southern face of Nab Scar the villagers of mediaeval Rydal gained the timber necessary for the building and repair of their farmsteads and the ungainly stunted forms of many of the trees testify to the right possessed by tenants of the manor to lop off the branches down to within ten feet of the ground. The Wordsworths loved these ancient oak woods of the Nab and in 1804 Dorothy, writing to De Quincey laments a senseless mutilation of them that had just taken place.

Differences as to their respective timber rights between a Liverpool gentleman who owned High House (the Rydal Mount of later days) and the Lady of the Manor had led to a frenzied topping and felling of trees by opposing factions of hirelings. Now the remaining hoary oaks decay in peace and about their feet the Lent lilies lie like moonlight on the slope. On a clouded day when wind and water flow together in a grey light from Rydal lake the sheets of daffodils in the Rash Field seem almost presumptuously joyous, lifting their miniature pale flowers undaunted between the sombre fells. and the ruffled pallor of the lake. Too lowly in stature to bow before to a wind that scented with wood smoke comes gusty from the west, now sweeping along the hilltops, now descending into the valley to shake the dead leaves yet clinging to the oak boughs - the daffodils that Wordsworth loved, fragile fleeting eternal flower to his memory through endless springs. Yet the great rock on which he sat by Rydal Water is already splintering into ruin.

E. M. W.

(Pictures from the 1965 village Scrapbook)